Of U-Prove and BBS

We, members of the W3C DIF BBS working group, have recently published the 3rd IETF draft of the BBS specification that integrates the optimizations of Stefano Tessaro and Chenzhi Zhu, reducing the signature and proof size (and proving the security of the scheme). I updated our implementation accordingly.

Given that I’m also developing U-Prove – a technology with similar characteristics – I’m often asked about the difference between the two schemes. This post sheds some light on this topic.

A bit of history

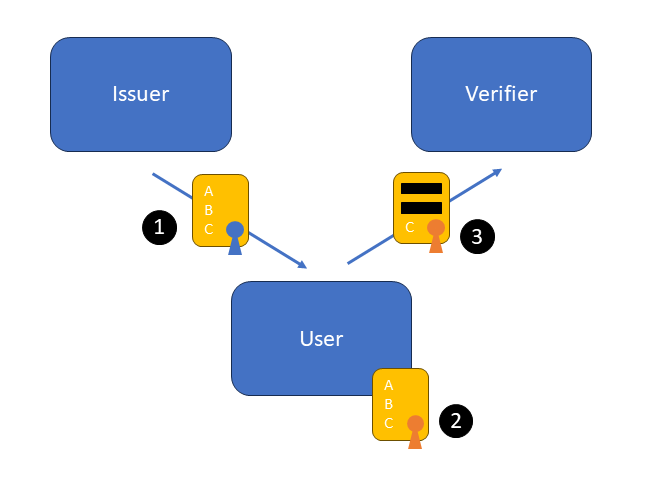

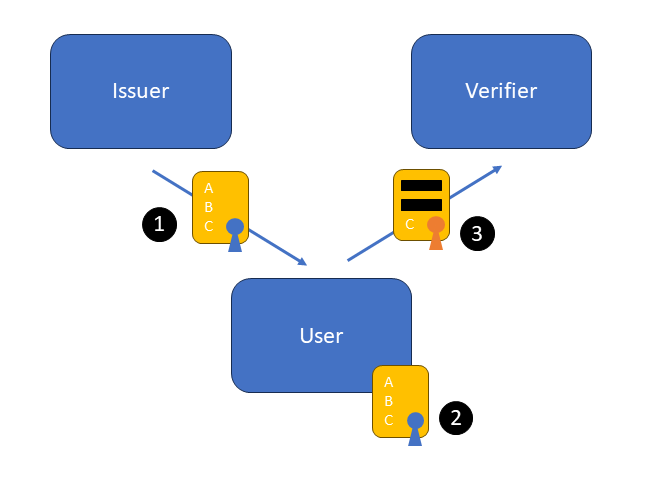

Cryptographers have long imagined how digital identity credentials should be built to provide both security and privacy: a user should be able to present a credential containing multiple attributes to various verifiers in a way that minimizes data disclosure, presenting only the required information; nothing more, nothing less. One important feature to support is the selective disclosure of the attributes, presenting only those needed for a particular transaction.1 Another important one is to prevent inescapable linkability between the issuance and presentation of the credential due to unique identifiers (see my previous post on the subject). We say that a system supports minimal disclosure if both principles are met.2

There are different mechanisms to achieve selective disclosure; for example the OAuth working group is currently working on a specification for JSON Web Tokens (you can experiment with my implementation). Achieving unlinkability, on the other hand, is more complicated.

David Chaum invented the concept of unlinkable signatures. His original technique, called blind signatures, allows an issuer to sign a message without learning its value. This scheme is useful when creating tokens with no attributes (as used in the privacy pass specification).3

Stefan Brands generalized the concept by creating restrictive blind signatures, which allows an issuer to unlinkably sign credentials containing multiple attributes, which can in turn be selectively disclosed to a verifier. This is the scheme at the core of the U-Prove technology.

Jan Camenisch and Anna Lysyanskaya later created the CL signature scheme, which allows an issuer to sign a multi-message credential, which can also be selectively disclosed to a verifier, proving that it was signed by the issuer without disclosing the signature itself. One benefit of using CL signatures is that a user could present their credential multiple times in an unlinkable manner (a.k.a., multi-show unlinkability). In contrast, multiple one-show U-Prove credentials must be obtained to achieve this feature. One issue with CL signatures, however, is their efficiency, as they are an order of magnitude slower and bigger than Brands’. CL signatures are the core of the Idemix system developed by IBM.

Finally, Dan Boneh, Xavier Boyen, and Hovav Shacham created the more efficient pairing-based BBS signature scheme, which after a few updates (including ideas from Camenisch and Lysyanskaya) became the basis for the current BBS specification.4

So, which one should I choose?

At a first glance, it seems that BBS’s multi-show unlinkability makes it more versatile, so it should be the obvious choice, but there are a few points to consider. It is important to understand where U-Prove and BBS fit in the protocol stack.

Brands’ signature scheme has been standardized in ISO/IEC 18370-2:2016. U-Prove builds on Brands’ signatures to create a credential system, specifying how issuers create their public parameters, and how users can obtain and present tokens. U-Prove must, however, be further profiled to be integrated into a framework or application. Over the years, we created X.509, SAML, and WS-Trust profiles to create privacy-preserving versions of these credentials. More recently, we created a JSON Framework to create privacy-preserving JSON Web Tokens and Signatures (and here is a proposal to integrate it into JSON Web Proofs).

BBS, similarly to Brands, is a low-level signature scheme, detailing how to sign and present messages. Some useful features are still in development, such as blind issuance of attributes and user-bound signatures. It would also need to be profiled in order to be integrated into higher-level components. There are efforts to integrate it into JSON Web Proofs, Verifiable Credential, and in version 2 of the Hyperledger anoncreds project (which evolved from the Idemix system).

U-Prove and BBS use different types of mathematical constructions. U-Prove can be implemented over any prime-order group, and currently uses standard elliptic curves making it easy to implement on any platform.5 BBS, on the other hand, uses pairing curves, which makes its implementation less efficient and more complicated. Fortunately, since the BBS specification uses the popular BLS curve used in many projects (e.g., ethereum and zcash), more libraries are becoming available simplifying its development.

Time is of the essence

Long-lived credentials should be revocable. We’ve learned from the PKI world that revocation is a difficult feature to deploy at scale. Indeed, deployers have a choice to use hard-to-maintain and bulky revocation lists (e.g., CRLs), privacy-reducing call-to-the-issuer (e.g., OCSP), or other in-between strategies (e.g., status list). The problem is exacerbated when dealing with minimal disclosure credentials, where we want to hide identifiable revocation identifiers from verifiers. Various revocation schemes have been designed to achieve this, the most promising ones using cryptographic accumulators to keep the revocation artifacts small.6 Like their conventional counterparts, these systems are also complicated and hard to deploy. Deployers of minimal disclosure credentials might therefore prefer to limit the validity period of the credentials and only issue short-lived ones, avoiding the need for a revocation system altogether. In this case, the multi-show unlinkability feature becomes less important, since the credentials need to be re-issued on a frequent basis.

Parting words

At the end of the day, the system requirements (including standards, performance, complexity) determine which cryptographic building block should be used in a given system (same as for any other cryptographic primitives we use). One-show unlinkability is often sufficient in systems where users want to establish a pseudonymous relationship with a verifier (e.g., when presenting the same identifier or claims in repeat visits). For users, it makes no difference which technology is used to present their application-level identity credential. If fact, we demonstrated this in the EU-funded ABC4Trust project where users were issued both U-Prove and Idemix credentials which could be used interchangebly and transparently to access various resources (under the hood, multiple U-Prove tokens are retrieved efficiently in-batch to maintain unlinkability across presentations).

The bottom line is that BBS signatures do not replace the need of simpler blind-signature schemes such as U-Prove, but rather complement the cryptographic toolbox with which we can create powerful privacy-preserving frameworks and the user-centric identity systems of tomorrow. I’m very excited by the progress we continue making in the BBS working group, and by the integration path into identity frameworks such as JSON Web Proofs and Verifiable Credentials, bringing the technology closer to deployment maturity.

Onward!

Footnotes

-

Selective disclosure of attributes can be generalized to present properties of attributes, without disclosing their values directly. For example, a user could prove that their name is not contained in a blocklist or that their credential expiration date is later than today, without disclosing either of the attributes. These predicate proofs, however, are more complicated, and we stick with the simpler notion of selective disclosure in this post, as supported by the core U-Prove and BBS specifications. You can learn more about some of these U-Prove extensions in this paper. ↩

-

These types of credentials are often referred to as anonymous credentials, but I prefer the term minimal disclosure credentials, as we rarely need full anonymity in identity scenarios. Minimal disclosure covers the full identity spectrum, from anonymity, to pseudonymity, to full identification, as required by the application. ↩

-

One could encode different attributes with few possible values using different issuer keys, but this is not scalable for general attribute schemas. This technique was used in early e-cash systems encoding different e-coin denominations. ↩

-

BBS was originally proposed by Boneh, Boyen, and Shacham in their Short Group Signature paper at Crypto 2004. The scheme was modified by Man Ho Au, Willy Susilo, and Yi Mu in their Constant-Size Dynamic k-TAA SNC 2006 paper, following an idea of Jan Camenisch and Anna Lysyanskaya from their Crypto 2004 Signature Schemes and Anonymous Credentials from Bilinear Maps paper. Finally, a few tweaks from Jan Camenisch, Manu Drijvers, and Anja Lehmann presented in section 4 of their TRUST 2016 Anonymous Attestation Using the Strong Diffie Hellman Assumption Revisited paper, and the optimizations by Stefano Tessaro and Chenzhi Zhu in their recent Revisiting BBS EuroCrypt 2023 paper lead to IETF BBS specification. ↩

-

The specifications recommends the prime curves from NIST, but any prime-order group curve could be used, such as FourQ or ristretto255. ↩

-

Most schemes originate from a design by Lan Nguyen, including this one we built for U-Prove, and the pairing-based ALLOSAUR and zk-SAM which could be used with BBS. ↩